Janet Lawson, MFT | February 21, 2014

[This is the second in a series of blog posts on the history, development, and methodology of Autistry by Janet Lawson and Dan Swearingen ]

Autistry Studios grew out of our experience as parents of an autistic son. Looking back, there were particular experiences that not only led us to create Autistry but also shaped the fundamental design of the program. In each of the following stories there is a common theme – a problem to be solved. In each case we thought hard about a solution and when those solutions worked, we found that the implications and the consequences of the decisions we made were often far larger than we initially realized. These experiences shaped much of what we do every day working with individuals of all ages with ASD. Our documentation of these events is sometimes vague and we apologize for that. For several of these events it was only much later that we realized their importance and, as we are not compulsive documenters of our daily lives, little details may have been forgotten. But we strive to be good storytellers and we hope that suffices.

Autistry Studios grew out of our experience as parents of an autistic son. Looking back, there were particular experiences that not only led us to create Autistry but also shaped the fundamental design of the program. In each of the following stories there is a common theme – a problem to be solved. In each case we thought hard about a solution and when those solutions worked, we found that the implications and the consequences of the decisions we made were often far larger than we initially realized. These experiences shaped much of what we do every day working with individuals of all ages with ASD. Our documentation of these events is sometimes vague and we apologize for that. For several of these events it was only much later that we realized their importance and, as we are not compulsive documenters of our daily lives, little details may have been forgotten. But we strive to be good storytellers and we hope that suffices.

Daring the Tantrum with Ian

If we had realized at the time how important this particular interaction with our son was going to be we would have done it earlier — and documented it better! When Ian was 9 years old there was a particular something he would do routinely after dinner – at this point we cannot for the life of us remember what irritating piece of ASD stubbornness it was. For the sake of discussion let us say that after dinner every night Ian insisted that we turn all the lights off in the house and retire to our bedrooms while he watched videos in his room. The point is that it was a ritual that was not flexible, not functional for the family, and Ian threatened to blow up into meltdown if we did comply.

We have come to see that this is a pattern of ritual experienced by many families with an ASD child. The signature is “I get to do this thing I want, when I want, the way I want or I will blow up! And make you [pick all that apply:] embarrassed, scared, afraid the neighbors will call the police, etc.”

We have come to see that this is a pattern of ritual experienced by many families with an ASD child. The signature is “I get to do this thing I want, when I want, the way I want or I will blow up! And make you [pick all that apply:] embarrassed, scared, afraid the neighbors will call the police, etc.”

After some time we realized that this was not getting better and we feared that Ian was not going to grow out of this particular habit. When we thought about it more, there were probably a dozen other rituals where Ian was doing the same thing: “Do what I want or I’ll blow!” Ian, like any smart human child had learned to have a measure of control over his world by threatening an angry or uncontrolled meltdown if he did not get what he expected. We think all children do this to some extent but an ASD child’s meltdown is the stuff of legend, as is their ability to be stubborn.

I know we got ourselves into this situation by inches. Over time it had grown into a real problem so we are very sympathetic to other families who find themselves in the same position. After some discussion we chose the after dinner ritual as the place where we were going to draw a line and insist that Ian give up this ritual. We were going to Dare the Tantrum.

Why would we ever consider doing this? The biggest reason was that we felt we should not continue to teach Ian that he could control us, or his school, or anyone in his life, by threatening a tantrum. We realized that in the end, it would be very destructive for Ian to be allowed to continue in this fashion.

We had to firmly move things to a better, more constructive place. We basically scheduled a fight with our son. For a couple nights in advance we warned and explained that the ritual he wanted was not helpful to mom and dad and we gave him several alternatives. He was not interested in compromise.

We will not call what we did “calling his bluff” because ASD kids do not bluff. The next night we drew the line. And Ian blew. Dan physically moved Ian back to his room and let him continue to tantrum. Again, Ian was 9 so we were able to physically manage him without damage to us or him. Ian yelled, screamed, and threw things for about 90 minutes until physically exhausted. We allowed him to do one of the alternatives we had offered and he finally went to bed.

We will not call what we did “calling his bluff” because ASD kids do not bluff. The next night we drew the line. And Ian blew. Dan physically moved Ian back to his room and let him continue to tantrum. Again, Ian was 9 so we were able to physically manage him without damage to us or him. Ian yelled, screamed, and threw things for about 90 minutes until physically exhausted. We allowed him to do one of the alternatives we had offered and he finally went to bed.

The next night we stood our ground again and this time he tantrumed for 20 minutes.

The next night after that he did not challenge the boundary.

Within a few months we realized that we had crossed into a new and wonderful place with our son. Ian was happier, calmer and more loving. Almost everything was going smoother with him. In the years since that time Ian has not had a single full power meltdown. He still complains, still yells back at us sometimes, and still can be very stubborn. But the out-of-control, the-neighbors-are-going-to-call-the-police meltdowns have been managed away.

From this we conclude that although Ian had been successful in managing us by tantrum, this success did not make him happier.

Or more secure. In looking back at Ian before this intervention we have concluded that Ian was feeling insecure and many of his old behaviors can be seen as insecurity, neediness and testing boundaries. Testing us.

Consistent with what many researchers have found with NT (neuro-typical) children, we strongly feel that appropriate and consistent boundaries are key to a happier and more stable child. Daring the tantrum is not easy. It is painful to hear one’s child screaming in seeming agony and there is a tremendous desire to give in and comfort the child. It helps to remember that this is a test and that the child needs to feel the strength and solidity of the boundary you, as parents, provide in order to feel safe. A child who feels safe can internalize that sense of safety and turn it into appropriate confidence and self-assuredness.

Appropriate boundaries mean that the rules you are imposing are not arbitrary, follow some sort of consistent logic, and the child understands them.

Consistent boundaries mean that once you have defined a boundary, you must not in any way signal that the child can overcome the boundary (overcome you), by tantrum or sheer stubbornness. Additionally, everyone in the child’s life must adhere to the same boundary (We discuss this more in later sections: we find that inconsistent boundaries across different environments and with different adults in a child’s life teaches them to lie and be sneaky).

Consistent boundaries mean that once you have defined a boundary, you must not in any way signal that the child can overcome the boundary (overcome you), by tantrum or sheer stubbornness. Additionally, everyone in the child’s life must adhere to the same boundary (We discuss this more in later sections: we find that inconsistent boundaries across different environments and with different adults in a child’s life teaches them to lie and be sneaky).

Do this when they are still small! Now that Ian is adult size, we also realize how important it is to settle this aspect of the relationship with the child while they are still physically small. An adult with adult strength having a meltdown will often require police involvement and involuntary commitment to a psychiatric facility. This has happened to other families.

Ian still pushes back when he does not agree with us and he can still be very stubborn but he is now forced to honestly negotiate with us. When we can, we work out a compromise with him. When we can’t compromise Ian has leaned that he must accept our decision because in the past, Ian had called our bluff and found we weren’t.

Arthur’s Gold Rush

One of the greatest lessons we learned as parents was the importance of entering our child’s world rather than forcing him to be in ours. Once we accepted his context we could communicate even abstract ideas and he could communicate back to us his understanding of the world. This brought rewards from unexpected places.

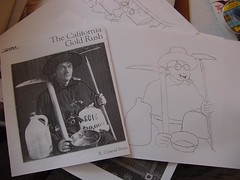

When Ian was in fourth grade it was time to learn about the California Gold Rush. Ian was mainstreamed part time into a fourth grade class. He had very low verbal ability compared to his classmates and the teacher and aides told us Ian was excused from any projects on this topic. They had no idea what he would be able to comprehend or accomplish.

We were frustrated with this situation. The school had no expectations that Ian could do anything like the other students. As long as Ian behaved, they were happy to have him. We could tell in our communications that they did not think Ian was very smart.

Without language, it is extremely difficult to learn some topics. History, especially in the past beyond the lifespan of any relative Ian knew was very hard for him to understand. Ian loved the Arthur the Aardvark series of books and videos. We had the idea of working with Ian to make an Arthur adventure that would teach Ian about the Gold Rush. We took famous gold rush photos and Ian traced those and substituted Arthur characters for the people in the photos. We made “Arthur’s Gold Rush Adventure”. Ian understood the story because he knew the characters – they were part of his world. He was very proud of his report and got an A+.

Without language, it is extremely difficult to learn some topics. History, especially in the past beyond the lifespan of any relative Ian knew was very hard for him to understand. Ian loved the Arthur the Aardvark series of books and videos. We had the idea of working with Ian to make an Arthur adventure that would teach Ian about the Gold Rush. We took famous gold rush photos and Ian traced those and substituted Arthur characters for the people in the photos. We made “Arthur’s Gold Rush Adventure”. Ian understood the story because he knew the characters – they were part of his world. He was very proud of his report and got an A+.

This reinforced our belief that you need to find a way into your child’s world and push from that place. It also established for us that our child’s work, more than his words, would establish and maintain his “personhood.”

This reinforced our belief that you need to find a way into your child’s world and push from that place. It also established for us that our child’s work, more than his words, would establish and maintain his “personhood.”

Our goal was simply to help Ian learn something comparable to what other students in his class were learning. The completed project also had some unexpected powerful positive side effects. At the next open house, we saw other teachers, students, and parents looking at Ian’s project in delight. We saw the most important thing that Ian got out of making the story: a huge change in how other people him.

Because of that success, the teachers had higher expectations for Ian and Ian worked harder to meet those expectations. His fellow students saw and appreciated our son’s quirky funny view of the world. This work gave Ian a way to communicate his personality and abilities beyond his limited verbal capabilities.

Traffic!

One day when Ian was 10 or 11 we were driving a client of an early Autistry program home. This client was a 20 year-old medium verbal autistic woman. We got stuck in traffic and Ian started complaining loudly and threatening a tantrum. Our client got very anxious and upset. We realized Ian did this routinely in traffic but we had grown used to it and ignored it. It took having a sensitive client in the car to for us to realize that our acceptance of Ian’s tantrums in traffic could not continue.

That evening we informed Ian that he had lost his computer privileges until he could behave himself when in our car in heavy traffic. He promised never to do it again. But we said that promises were not good enough and that he would have to show us he could handle the frustration of traffic. He was VERY unhappy and upset with us. But he thought about it.

That evening we informed Ian that he had lost his computer privileges until he could behave himself when in our car in heavy traffic. He promised never to do it again. But we said that promises were not good enough and that he would have to show us he could handle the frustration of traffic. He was VERY unhappy and upset with us. But he thought about it.

The next day Dan came home from work and Ian ran up to him and said “we need to go find some traffic so I can get my computer back!” Dan turned around and took him out to find some heavy evening traffic. Ian sat quietly in the car the whole time. Ian got his computer privileges back and has never tantrumed in traffic since. We were happy — and shocked it had worked.

The lesson to us: it is important to create a dynamic where the child practicing the desired behavior grants them the privilege they want. Traditional punishment is based on focusing on the “bad thing:” “I will take away [thing they want] because you did [bad thing].”

We have found that this mode of discipline often does not work with ASD children. It seems to make them fixate on the bad thing, and fixate on what you took away, and does little to get them to fixate on behavior that would make things better.

Instead we suggest trying “You have already lost [thing you want]. Do [better behavior] for [specified amount of time] and you will get [thing you want] back.” You are also saying “use your brains and abilities to get what you want back.” We have found that the child always understands the implicit “if you do [bad thing] again, you will again lose [thing you want].

That Ian was able to challenge himself to tolerate his traffic frustration encouraged us to have higher long term expectations for him. We realized that for Ian when presented with a desired goal, given defined boundaries and appropriate support he could change negative behaviors.

That Ian was able to challenge himself to tolerate his traffic frustration encouraged us to have higher long term expectations for him. We realized that for Ian when presented with a desired goal, given defined boundaries and appropriate support he could change negative behaviors.

We began to wonder if our personal parental lessons could be of value to other families.

Category: Writing |

1 Comment »

Tags:

In any case, we knew Ian needed focus. As Ian approached eighth grade we started looking at choices for high school. Ian had been with a large cohort of regular ed neighborhood students since fourth grade. They knew Ian, liked him and looked out for him. Almost all of these students were going to be moving to Redwood High School across the street from the middle school. However, our high school district has concentrated their services for autistics and other special education programs at Drake High School further away and with an almost totally new group of students.

In any case, we knew Ian needed focus. As Ian approached eighth grade we started looking at choices for high school. Ian had been with a large cohort of regular ed neighborhood students since fourth grade. They knew Ian, liked him and looked out for him. Almost all of these students were going to be moving to Redwood High School across the street from the middle school. However, our high school district has concentrated their services for autistics and other special education programs at Drake High School further away and with an almost totally new group of students. Ian wanted to go to Redwood with his cohort. The District wanted Ian to go to the other school. This presented us with a difficult but clear choice. With all the special education resources at Drake, Ian would have one-on-one support and classes modified to his level. At Redwood, Ian would have no one-on-one support and only a slightly modified classroom experience. The district’s choice would be better for Ian’s education. Ian’s choice would be better for his social skills and learning independence.

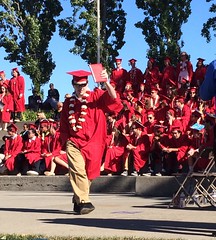

Ian wanted to go to Redwood with his cohort. The District wanted Ian to go to the other school. This presented us with a difficult but clear choice. With all the special education resources at Drake, Ian would have one-on-one support and classes modified to his level. At Redwood, Ian would have no one-on-one support and only a slightly modified classroom experience. The district’s choice would be better for Ian’s education. Ian’s choice would be better for his social skills and learning independence. We made the choice that Ian’s education was going to be a long haul. We realized that our goal for high school was that Ian acquire the skills to be able to continue his education after high school. That meant enjoying school enough to want to continue. Ian attended Redwood high nearby and left in 2014 with a certificate of completion.

We made the choice that Ian’s education was going to be a long haul. We realized that our goal for high school was that Ian acquire the skills to be able to continue his education after high school. That meant enjoying school enough to want to continue. Ian attended Redwood high nearby and left in 2014 with a certificate of completion. Frankly, Ian is not fully on board with the plan that he attend community college part time and work part time, possibly for many years. The near term goal is a GED and possibly attending a four-year college afterwards. When asked, Ian’s idea of college and his living situation is based on the movie “Animal House.” He sees himself living with a group of young people having fun.

Frankly, Ian is not fully on board with the plan that he attend community college part time and work part time, possibly for many years. The near term goal is a GED and possibly attending a four-year college afterwards. When asked, Ian’s idea of college and his living situation is based on the movie “Animal House.” He sees himself living with a group of young people having fun.

We have come to see that this is a pattern of ritual experienced by many families with an ASD child. The signature is “I get to do this thing I want, when I want, the way I want or I will blow up! And make you [pick all that apply:] embarrassed, scared, afraid the neighbors will call the police, etc.”

We have come to see that this is a pattern of ritual experienced by many families with an ASD child. The signature is “I get to do this thing I want, when I want, the way I want or I will blow up! And make you [pick all that apply:] embarrassed, scared, afraid the neighbors will call the police, etc.” We will not call what we did “calling his bluff” because ASD kids do not bluff. The next night we drew the line. And Ian blew. Dan physically moved Ian back to his room and let him continue to tantrum. Again, Ian was 9 so we were able to physically manage him without damage to us or him. Ian yelled, screamed, and threw things for about 90 minutes until physically exhausted. We allowed him to do one of the alternatives we had offered and he finally went to bed.

We will not call what we did “calling his bluff” because ASD kids do not bluff. The next night we drew the line. And Ian blew. Dan physically moved Ian back to his room and let him continue to tantrum. Again, Ian was 9 so we were able to physically manage him without damage to us or him. Ian yelled, screamed, and threw things for about 90 minutes until physically exhausted. We allowed him to do one of the alternatives we had offered and he finally went to bed. Consistent boundaries mean that once you have defined a boundary, you must not in any way signal that the child can overcome the boundary (overcome you), by tantrum or sheer stubbornness. Additionally, everyone in the child’s life must adhere to the same boundary (We discuss this more in later sections: we find that inconsistent boundaries across different environments and with different adults in a child’s life teaches them to lie and be sneaky).

Consistent boundaries mean that once you have defined a boundary, you must not in any way signal that the child can overcome the boundary (overcome you), by tantrum or sheer stubbornness. Additionally, everyone in the child’s life must adhere to the same boundary (We discuss this more in later sections: we find that inconsistent boundaries across different environments and with different adults in a child’s life teaches them to lie and be sneaky).

That evening we informed Ian that he had lost his computer privileges until he could behave himself when in our car in heavy traffic. He promised never to do it again. But we said that promises were not good enough and that he would have to show us he could handle the frustration of traffic. He was VERY unhappy and upset with us. But he thought about it.

That evening we informed Ian that he had lost his computer privileges until he could behave himself when in our car in heavy traffic. He promised never to do it again. But we said that promises were not good enough and that he would have to show us he could handle the frustration of traffic. He was VERY unhappy and upset with us. But he thought about it. That Ian was able to challenge himself to tolerate his traffic frustration encouraged us to have higher long term expectations for him. We realized that for Ian when presented with a desired goal, given defined boundaries and appropriate support he could change negative behaviors.

That Ian was able to challenge himself to tolerate his traffic frustration encouraged us to have higher long term expectations for him. We realized that for Ian when presented with a desired goal, given defined boundaries and appropriate support he could change negative behaviors. Our son is autistic and his autism has driven much that we have done and learned. Ian was born early in 1995 while we were living in Bloomington, Indiana. Dan was a Ph.D. candidate at Indiana University studying Astrophysics. Janet was a librarian at the local public library and was working on her Masters degree in Library and Information Science at IU. Towards the end of the pregnancy Janet’s blood pressure started to increase and she was diagnosed with preeclampsia. As her due date approached her doctors worked to induce a normal delivery. After nearly two weeks Janet’s condition deteriorated to eclampsia and Ian was delivered by emergency c-section. Ian was full term and a very healthy baby at birth.

Our son is autistic and his autism has driven much that we have done and learned. Ian was born early in 1995 while we were living in Bloomington, Indiana. Dan was a Ph.D. candidate at Indiana University studying Astrophysics. Janet was a librarian at the local public library and was working on her Masters degree in Library and Information Science at IU. Towards the end of the pregnancy Janet’s blood pressure started to increase and she was diagnosed with preeclampsia. As her due date approached her doctors worked to induce a normal delivery. After nearly two weeks Janet’s condition deteriorated to eclampsia and Ian was delivered by emergency c-section. Ian was full term and a very healthy baby at birth. But as the months passed he began to miss the usual milestones of speech development. We had one of those “What to Expect…” books and noted with increasing worry and dread each “normal” milestone he missed. He did not babble in a speech-like way in the early months. He was not drawn to noise-making toys nor did he imitate different speech sounds. He seemed totally mystified by games of Peek-a-Boo. But he always smiled. He made eye contact. And he loved to be held. Ian seemed to communicate without words. And though we thought his utter fascination with cupboard door hinges, the pliability of a sheet of paper, or the concentric ripples in a dog’s water dish was a bit eccentric we simply chalked it up to being the son of a scientist. We took comfort in the stories that Einstein didn’t speak until he was 3 years old. Even though Ian never measured up to the What to Expect timelines he nevertheless developed into an attractive, engaging and affectionate child.

But as the months passed he began to miss the usual milestones of speech development. We had one of those “What to Expect…” books and noted with increasing worry and dread each “normal” milestone he missed. He did not babble in a speech-like way in the early months. He was not drawn to noise-making toys nor did he imitate different speech sounds. He seemed totally mystified by games of Peek-a-Boo. But he always smiled. He made eye contact. And he loved to be held. Ian seemed to communicate without words. And though we thought his utter fascination with cupboard door hinges, the pliability of a sheet of paper, or the concentric ripples in a dog’s water dish was a bit eccentric we simply chalked it up to being the son of a scientist. We took comfort in the stories that Einstein didn’t speak until he was 3 years old. Even though Ian never measured up to the What to Expect timelines he nevertheless developed into an attractive, engaging and affectionate child. For financial reasons Dan quit school before finishing his Ph.D. but found that his programming skills were in very high demand back where we grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area. We moved the family to Marin County in 1997. Ian was two and a half. We did not know any pediatricians in the area so Janet somewhat randomly chose the first one found in the health insurance providers list. This doctor happened to specialize in developmental pediatrics and their first appointment, a simple well-baby checkup, stretched into nearly three hours and ended with the doctor solemnly stating: “I think we need to consider the possibility that your son is autistic.”

For financial reasons Dan quit school before finishing his Ph.D. but found that his programming skills were in very high demand back where we grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area. We moved the family to Marin County in 1997. Ian was two and a half. We did not know any pediatricians in the area so Janet somewhat randomly chose the first one found in the health insurance providers list. This doctor happened to specialize in developmental pediatrics and their first appointment, a simple well-baby checkup, stretched into nearly three hours and ended with the doctor solemnly stating: “I think we need to consider the possibility that your son is autistic.”

She considered Ian to be a “low-functioning autistic”. The worst diagnosis they give. Dan remembers that the only literature he could find was that people with that diagnosis had an 80% probability of being institutionalized as adults. At that time there was very little literature to look at and none was particularly encouraging. UCSF had a list of many things they wanted Ian to do with them but we quickly saw that all they were interested in was studying Ian, not treating him. The lack of guidance as to what we should do was very upsetting to us.

She considered Ian to be a “low-functioning autistic”. The worst diagnosis they give. Dan remembers that the only literature he could find was that people with that diagnosis had an 80% probability of being institutionalized as adults. At that time there was very little literature to look at and none was particularly encouraging. UCSF had a list of many things they wanted Ian to do with them but we quickly saw that all they were interested in was studying Ian, not treating him. The lack of guidance as to what we should do was very upsetting to us. Ian, like most young children, loved Winnie the Pooh. When he first began to talk he would stay up all night reciting long passages from the Disney movies. His lilting sing-song voice was not a good lullaby so Janet was up all night with him. So she too memorized the Winnie-the-Pooh dialogue. One night as Ian recited the well worn lines Janet took the part of Tigger – “The wonderful thing about tiggers, is tiggers are wonderful things…” Ian whipped his head around, looked her right in the eye…and then burst into laughter. She had entered his world. That was the first night he fell asleep before 3am. Janet had found a way to connect with him in that very special world of his imagination.

Ian, like most young children, loved Winnie the Pooh. When he first began to talk he would stay up all night reciting long passages from the Disney movies. His lilting sing-song voice was not a good lullaby so Janet was up all night with him. So she too memorized the Winnie-the-Pooh dialogue. One night as Ian recited the well worn lines Janet took the part of Tigger – “The wonderful thing about tiggers, is tiggers are wonderful things…” Ian whipped his head around, looked her right in the eye…and then burst into laughter. She had entered his world. That was the first night he fell asleep before 3am. Janet had found a way to connect with him in that very special world of his imagination. As the parents of a newly diagnosed autistic child we entered a world where it felt like every week brought a new Thing We Could Do to Cure Our Child. Music! Horses! Computer games! No computer games! Magnets! We looked into all of them. Everyone we knew sent us literature they had found. “Have you tried….?” There was constant guilt that we were not doing enough. Constant frustration when the weekly “cure” turned out to work on ONE child in the entire world. And then friends would keep sending us information about that same cure for the next month. We came to call this: living with the threat of a cure (that you did not take advantage of!).

As the parents of a newly diagnosed autistic child we entered a world where it felt like every week brought a new Thing We Could Do to Cure Our Child. Music! Horses! Computer games! No computer games! Magnets! We looked into all of them. Everyone we knew sent us literature they had found. “Have you tried….?” There was constant guilt that we were not doing enough. Constant frustration when the weekly “cure” turned out to work on ONE child in the entire world. And then friends would keep sending us information about that same cure for the next month. We came to call this: living with the threat of a cure (that you did not take advantage of!). In Ian’s schooling we generally received good service by collaborating with the districts as best we could. We tried wherever possible to provide extra help and materials to support the classroom teachers. And we mostly managed without huge legal battles – that is not to say that there were never heated negotiations. But the outcome was always agreed to be in Ian’s best interest. Ian is currently a senior in high school and will graduate with a certificate of completion with the same group of kids he has been with since fourth grade.

In Ian’s schooling we generally received good service by collaborating with the districts as best we could. We tried wherever possible to provide extra help and materials to support the classroom teachers. And we mostly managed without huge legal battles – that is not to say that there were never heated negotiations. But the outcome was always agreed to be in Ian’s best interest. Ian is currently a senior in high school and will graduate with a certificate of completion with the same group of kids he has been with since fourth grade.